This week’s guest blog is from Kathleen E. Kennedy, Associate Professor of English at Penn State Brandywine on Pierre Bersuire’s Repertorium morale.

Durham Cathedral’s copy of Pierre Bersuire’s Repertorium morale is an excellent introduction to English ecclestical book production in the late Middle Ages. Enormous compendia like the Repertorium were laboriously compiled to assist in crafting one of the most widely popular forms of late-medieval media: sermons. A sort of sermon-maker’s dictionary, the Repertorium offered biblical facts under keywords organized in alphabetical order.

Durham’s copy of the Repertorium is especially poignant, as it was apparently left to the cathedral library by English chancellor and Durham bishop Thomas Langley, just before his death in 1437. Langley’s own life is just as exempletive as the volume, offering an excellent example of the careerist politician-churchman that was vital to late medieval statesmanship. Yet, for all of Langley’s unflagging support for the Lancastrian dynasty, he was also a man of the faith of his time. Recognizing that his political career had left his ecclesiastical duties a distant second for many decades, he turned in the last decade of his life to Durham, and sought to devote his considerable energies to his see at last.

Providing the library with a copy of the Repertorium was precisely the sort of work Langley might have been particularly keen on in this decade, as the text could materially assist in the writing and delivery of quality sermons long after the bishop was gone. Moreover, donating a copy of the Repertorium demonstrated both wealth and personal network, and such ostentatiously calculated piety was standard practice in Langley’s era. The substantial quantity of parchment and extended services of copyists needed for such an undertaking (almost 2500 pages of text) cost dearly. Further, one had to have the connections necessary in order to find a complete copy of the Repertorium to use as an exemplar in the first place. After a lifetime in government service, Langley had more than deep enough pockets, and his decades in London furnished him with the contacts to complete this major commission.

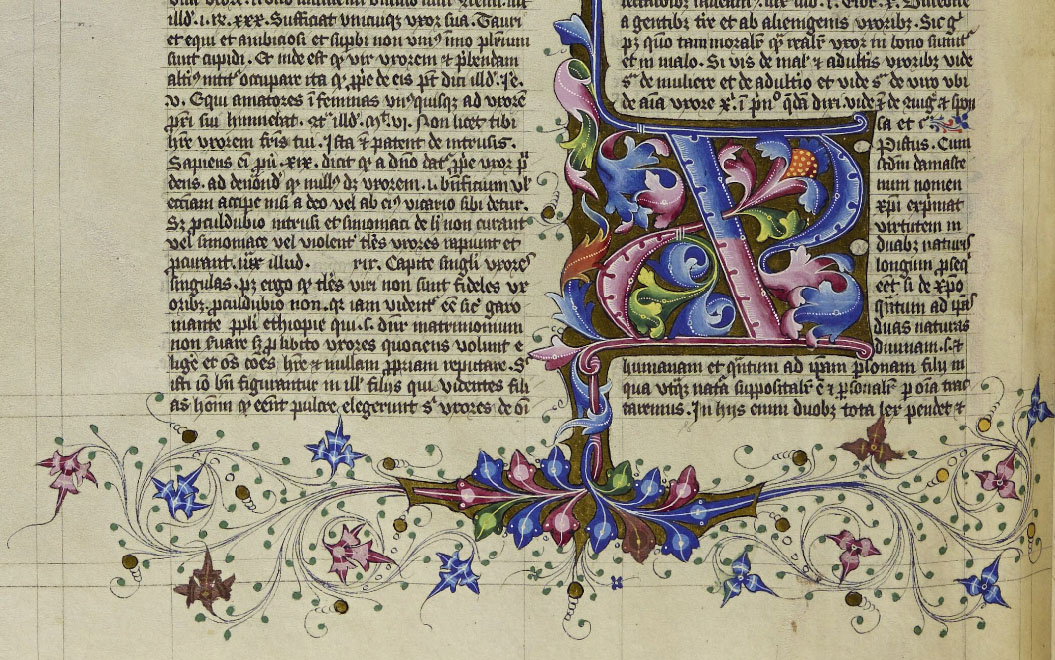

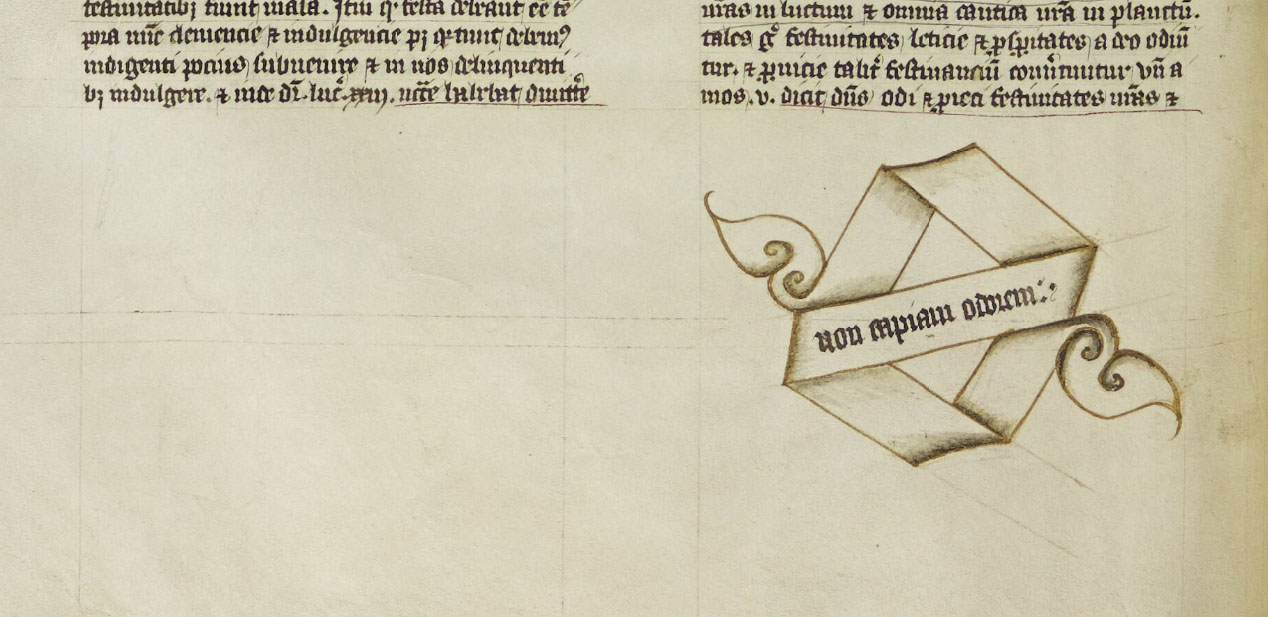

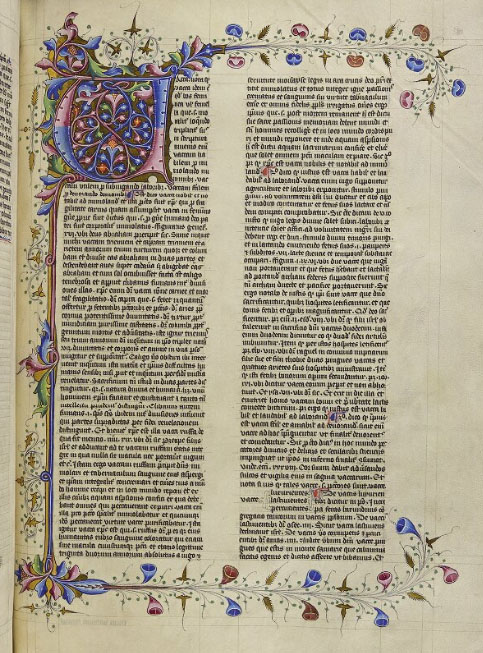

The three-volume set demonstrates various strategies that book artisans employed in order to fill large orders within a reasonable span of time. Each volume was completed by a different team of artisans. The Repertorium as a text was primarily utilitarian, and so, at minimum, required only basic ink decoration as visual cues to the text’s organization. However, Langley also purchased some more expensive, illuminated initials for each volume, highlighting the beginning of some of the alphabetical sections. These initials are in three different styles. The first is a standard style used in French manuscripts of these decades, and the flourishing is also continental in style, rather than being English. The scribe signed his name, Johnnes de Fonte, in a scribal colophon more commonly used by continental scribes than English scribes. While entirely professional, the second volume’s script is less elegant than de Fonte’s hand, and the flourishing is English in style, including elaborately decorated catchwords on shaded scrolls. This volume’s illuminated initials show an English style and distinctive use of green on the stalks of sprays. This volume might reward closer study to see if it can be related to volumes known to be decorated in the North.

The third volume, now split into two parts (part one here, part two here), provides our concentration for this post. Its script is even more workmanlike than that of the second volume. Alone of the three, we know quite a bit about the artists hired to decorate a half-dozen borders in this volume. In almost every respect this was an unusual project for the artists, known as the Followers of the Corpus Master, to have decorated. Active in the second quarter of the fifteenth century, the Followers made books for very elite clientele, including the French dauphin, Charles d’Orlèans, and a series of chancellors and high clergy including Thomas Langley, Thomas Bourchier, and John Wheathamstead. Yet, the majority of their body of work were small devotional manuscripts: books of hours and psalters. They produced very few two-column manuscripts such as the Repertorium, and exceptions, like their copies of the Wycliffite New Testament and the massive Prayerbook of Charles d’Orlèans, prove the rule. The prayerbook illustrates an even larger team effort than the Repertorium. According to Gilbert Ouy (2000), it seems to have been ordered and produced very rapidly just before Charles’ return to France in 1440, and Kathleen Scott (1996) believed it took many scribes and over a dozen artists to complete its thousand pages. As in the Prayerbook, the Followers of the Corpus Master decorated only a few initials in the Repertorium. I have suggested elsewhere that at least some members of the Followers were clergy and thus not supporting themselves on the proceeds of their art (2017). Commissions like the Repertorium further support that hypothesis. While laypeople increasingly crafted books in the later Middle Ages, clergy continued to serve as book artisans as well, creating both simple utilitarian volumes and luxurious art objects.

According to Scott, the Followers, and their teacher the Corpus Master, were innovators in English art, introducing a range of continental motifs and colors to England while producing delicate, lively borders and initial art in a recognizably English style. The group’s high-end clientele seem to have enjoyed this hybrid style, and these features spread widely into English art over time. In the Repertorium we see a relatively narrow range of these motifs, suited to the limited number of initials and borders completed by these artists. Each spray features a different colored motif that is further decorated with small, gold motifs. The borders shows capable, if restrained dimensionality–acanthus leaves twine about bars, and gold backgrounds are pierced by vines developing into sprays. Floral aroid forms reigned over English style for decades beginning in this period, including in other examples of the Followers’ work, but appear here in small forms, and in moderation. From border to border straight sprays vary with lively curling sprays that hallmark this group’s style, and the green lobes topped with stacks of bubble-like circles ending in a lobed tail increase the light, almost frothy effect on the page. In comparison to the sprays, in this volume the initials are large and fine, but not especially innovative.

I frequently claim that one can teach an entire course with any medieval manuscript, but Durham’s copy of Peter Bersuire’s Repertorium is unusually rich. Through it we can explore both late medieval English mortuary piety and popular media and religion. Considered together, these volumes offer illustrations of a wide range of book producing techniques, and enable a relatively unusual view into the work of a specific group of illuminators. Though its physical size may be daunting, these volumes richly repay the time that we spend with them.

Kathleen E. Kennedy

Associate Professor of English, Penn State Brandywine