In the next few months and years you may see more and more information on pigments available on the Durham Priory Recreated website. Collected by ‘Team Pigment’ – a group of chemists and historians from Durham and Northumbria Universities – this information aims to tell the viewer which exact pigments or dyes were used to create the splendid illustrations contained within the manuscript collection. In this blog post I try to answer the question of why ‘Team Pigment’ has such an interest in this research.

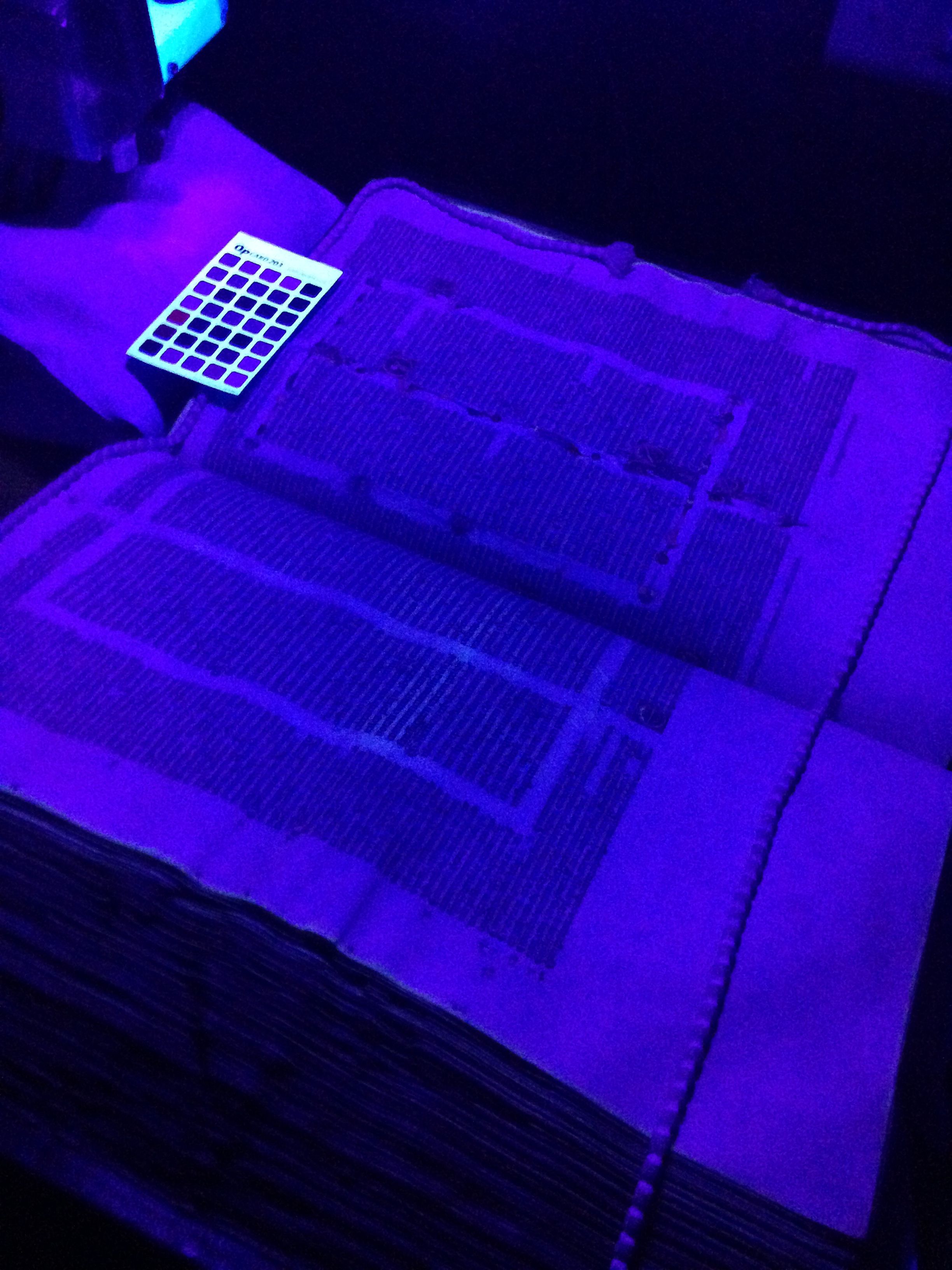

In the past few centuries, scientific techniques have been employed to understand further the technology that was employed in the making of these magnificent books. At first, the field was invasive – samples were taken, books were unbound, and parchment was cut. Some nineteenth century scholars even employed strange methods to learn more – in one case tipping strongly brewed tea onto the surface of a manuscript in an effort to reveal the secrets that lay beneath the surface! However, these techniques have thankfully been recognised as damaging and detrimental and now there are an increasing number of non-invasive analytical scientific techniques that can be employed.

One area of manuscript studies that has benefitted immensely from this analysis is the study of the inks and pigments used to write and decorate these great works. In the field of history, knowledge of which pigments were used to create illustrations can answer many questions. Individual illuminations and other artworks can be assigned to individual scribes or illuminators. Knowledge of scribal practice can tell us more about how manuscripts were created, the transmission of manuscripts across the world, and the itinerary of scribes/illuminators. Trends in pigment use over time and place can show the creation of and changes in trade routes and the impact of cultural and religious events on commerce can be further established.

Aside from history, pigment analysis also has many conservation implications as correct identification of pigments used allows increasingly sensitive conservation techniques to be applied. There are also wider applications of the use of pigment identification – to detect fraudulent works of art where anachronistic pigments are used, for example.

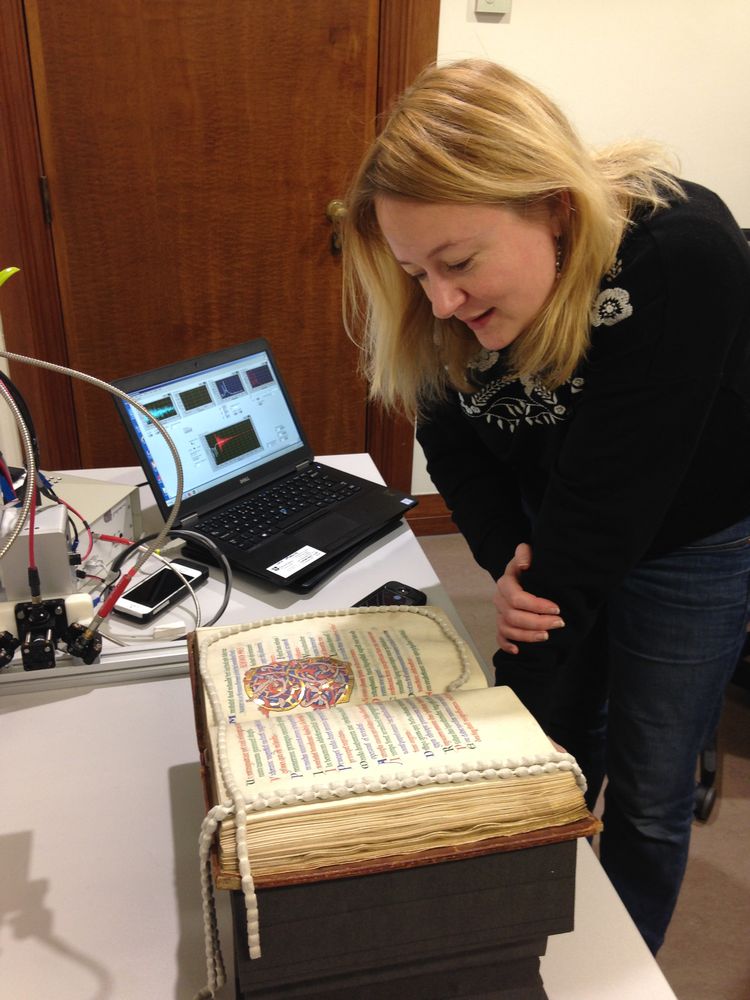

As the application of non-invasive analytical techniques on priceless manuscripts has become more commonplace, and more and more scholars are turning to science to answer the questions they are asking, technology has had to keep pace in order to provide the answers. At the University of Durham, the capabilities of the Raman spectrometer that occupies an entire room and weighs half a ton, are replicated by a portable spectrometer that fits into two suitcases. Advances in this portability mean that the equipment can travel nationally and internationally to a manuscript, and examination can take place in situ rather than the manuscript having to move.

Whilst manuscripts are not quite as fragile as one might suppose (one could take a match to parchment and would have trouble keeping a fire burning) the illustrations themselves are sometimes not standing the tests of time. Past exposure to sunlight, water damage, rough treatment and the passage of time itself can degrade the pigment colour or composition, or both, and pigments sometimes flake off the writing support. Sometimes pigments can “eat” through the parchment itself, or react with other pigments to produce unfavourable effects, and it is conservation research that aims to halt this.

Louise Garner, Durham, July 2018