In short, the answer to the question, ‘Who needs canon law?’ is, ‘Everyone.’ Canon law is, as a practical discipline, the body of regulations (Latin: regulae or the Greek canones) that govern church life. As a realm of knowledge, canon law is the study of the ordering of relationships amongst human beings, clerical and lay, from bishops, popes, and kings, to monks, ‘ordinary’ lay people, and subdeacons.

It never really went out of fashion in the Middle Ages. Even before the strengthening of papal power and effective authority in the eleventh and twelfth centuries, everyone had an interest in canon law so as to know their duties and their rights, to seek an insight into what a just society might look like, a society ordered under the headship of Christ.

At Durham, William of St-Calais needed it to be able to maintain his own rights and position in the face of opposition from King William Rufus. Canon law enabled him to appeal to the pope and made him claim, in 1088, that an assembly of laymen was not legally competent to try him. He used the manuscript now Cambridge, Peterhouse 74, a copy of what scholars call Collectio Lanfranci, a canon law book brought over from Normandy with Lanfranc of Bec (Archbishop of Canterbury, 1070-89).

William of St-Calais’ successor, Ranulf Flambard (Bishop of Durham 1099-1128) needed canon law because he was involved in the disputes between Canterbury and York over whether or not Canterbury was Metropolitan or Primate over all of Britain or just over the South, and York thus Metropolitan in the North, independent of Canterbury. During his episcopate, Durham Cathedral Library B.IV.18 was written in Canterbury, and probably came here soon after — this contains a lot of canon law, including the Canterbury forgeries, forged documents that pressed Canterbury’s claims as Metropolitan of all Britain.

In the mid-1100s, William Cumin tried to have himself forcibly installed as Bishop of Durham with the support of King Malcolm Canmore of Scotland. Armies were involved. People died. His opponent was William of Ste Barbe, who won in the end not through force of arms but through canon law, as described in additions to Symeon of Durham’s history of the Church of Durham.

The monks of Durham also needed canon law, especially in the later 1200s when they came into dispute with Antony Bek (Bishop of Durham, 1284-1310), and could produce their own documents and cite procedure to press their against him.

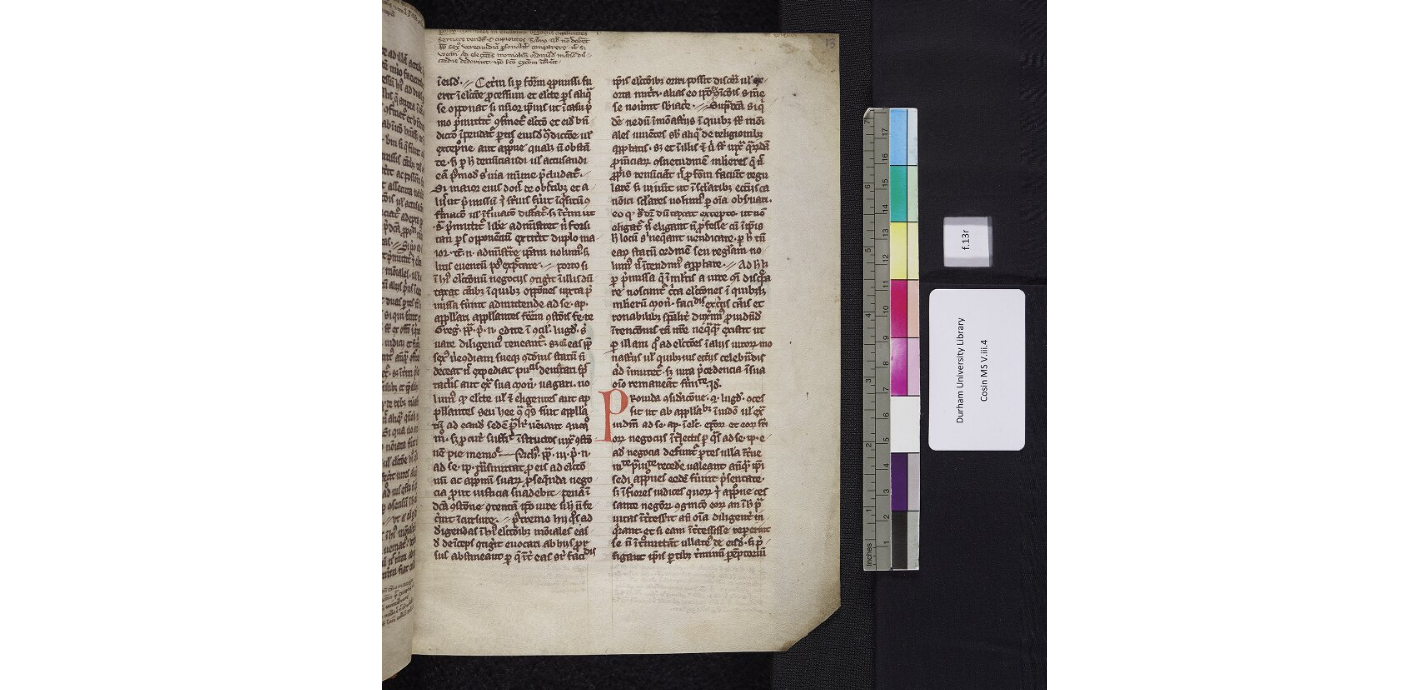

Not only can we find the use of canon law in narrative sources, we need look no further than Durham’s manuscripts themselves. So far, the only canon law manuscript is a copy of the Liber Sextus of Boniface VIII, which is a systemisation of the decretals of Boniface VIII (Pope 1294-1303) that formed, along with five other volumes of decretals and Gratian’s Decretum, the Corpus Iuris Canonici.

Gratian’s Decretum, composed around 1140, is the most popular canon law book of the Middle Ages. Durham Priory had five copies. It also had a copy of Burchard of Worms (DCL B.IV.17), which was very popular before Gratian, as well as copies of the work associated with Ivo of Chartres (who comes between Burchard and Gratian). I won’t bore you with the gory details, but there are canon law books associated with Durham Priory from its (re)foundation by William of St-Calais in 1083 to the decretals of Hadrian VII, printed in 1527.

The big names of canon law from that era are all represented, and some of these manuscripts, especially illuminated copies of Gratian, are real treasures. My preliminary count has found thirty-three manuscripts of canon law, one printed book, and three volumes of Roman law.