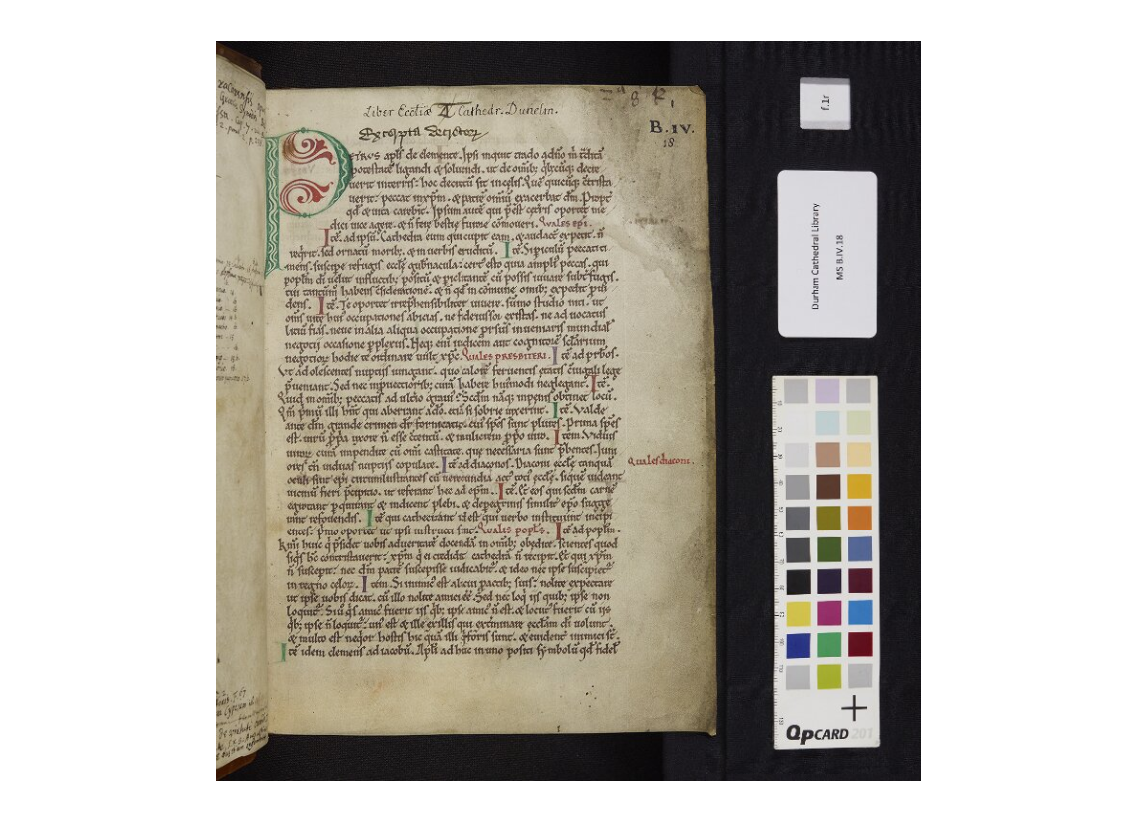

Durham Cathedral Library, MS B.IV.18, written in the early twelfth century, begins with what canon law scholars call the ‘Canterbury Abridgement’ of Collectio Lanfranci, which would be the canonical collection Lanfranc of Bec brought with him to England and dispersed whilst Archbishop of Canterbury (1070-1089). This manuscript and the other one that contains the abridgement, Lambeth Palace MS 351, were written at Christ Church, Canterbury, based on palaeography. The abridgement is followed by a selection of letters from Gregory the Great.

As Martin Brett has discussed (see bibliography at bottom), the Canterbury Abridgement is not especially useable. The excerpts from papal letters and conciliar canons all just run together with no headings to help guide the interested reader. Not only this, I would also say it is not particularly useful, not, at least, the way we might expect a canon law book to be used by a reader.

Living in an age of reference works, handbooks, and manuals, we expect an abridgement of Lanfranci to be something that someone could take up, skim through, and find interesting bits of canon law, perhaps to help him in an upcoming trial or to sort out whether he could marry his deceased brother’s widow. Unfortunately for such a reader, not only is the Canterbury abridgement entirely unsuited to this task, it is likely to be completely useless, including as it does such unhelpful pieces of church regulation as Leo the Great’s statements on what to do if someone has been captured by pagan barbarians and forced to participate in feasts in honour of pagan gods.

My hypothesis is that the Canterbury Abridgement is not canon law. It is theology.

It is very common to say that canon law did not exist as a separate discipline from theology before Gratian and the rise of the schools of law, starting in Bologna in the mid-1100s. Yet we continually treat the pre-Gratian canonical collections and the body of church canons as ‘canon law’. Perhaps this is the wrong way of going about it.

The first step in testing this hypothesis is actually reading all of the Canterbury Abridgement (I’ve yet to do this). The second step I have already taken — considering the rest of the contents of the manuscript. These contents are what made my hypothesis arise. After the regulatory material, which also includes the Concordat of Worms (1122), DCL B.IV.18 includes the Cena Cypriani, which is a long, biblical allegorical amusement piece, the Canterbury Forgeries, Hugh of St Victor in a later hand, excerpts from Augustine, then more ‘canon law’ material.

What does all this regulatory material have in common with the Cena and Augustine?

That is a theological question. The canons of the church are the application of theological principles to concrete human situations, are they not? Theology, such as Augustine on the Trinity, is the application of human reason to the questions of God. Both of them seek order. The former seeks the right ordering of human relationships. The latter considers the ordering of divine relationships. They interact with each other more than one would think. (On this, think on Wei, Gratian the Theologian.)

Iustitia and rectitudo — these are part of the divine oikonomia, are they not? And they are meant to be part of the human oikonomia operating out of divine gratia.

What that means in the context of this manuscript — that remains to be seen.

Bibliography

Image provided by Durham Priory Library Project – a collaboration between Durham University and Durham Cathedral

Brett, Martin. ‘The Collectio Lanfranci and Its Competitors’, in Intellectual Life in the Middle Ages: Essays Presented to Margaret Gibson, ed. Lesley M. Smith, Benedicta Ward (London 1992), 157-174, at 161.

Evans, G. R. Law and Theology in the Middle Ages. London, 2002.

Wei, John C. Gratian the Theologian. Washington, D.C., 2016.