It feels appropriate to be writing this brief post in today’s cathedral library, the Sharp Library, underneath the immense wooden timbers of the roof in the old monastic dormitory. I’m looking up at the same beamed ceiling that all the monks at Durham would have known although the current windows and the book-presses are all much later additions. Still, they give the lovely illusion that there has been an unbroken chain of scholarship in this room from the days when each monk had his windowed cubicle with a bed and a desk and the novices had the cubicles without windows through to today’s library where I have a laptop and a view towards Palace Green if I’m lucky. Some of the books that were read by the monks are still kept next door in the old refectory. (The links have pictures if you’re curious).

I’ve been thinking about space lately. Monastic space was of course highly regulated in a variety of ways, in terms of who could be where but also where monks had to be. What must it have been like when the monastery was officially gone and only 24 of the around 60 monks were still there in the new cathedral’s community? The prior’s house pretty seamlessly became the deanery. His life had always been slightly separate from the rest of the monastery and so it was easy for the last prior, Hugh Whitehead. But each of the canons needed a house of his own rather than living a communal life in the dormitory. They almost seem to have camped out in the old monastic buildings as they set up their own separate households. The Rites of Durham say that one canon took the kiln used to dry out grain for his house. The infirmary and guesthouse disappear pretty quickly. Canons would now host guests in their own houses as they were created within the larger buildings.

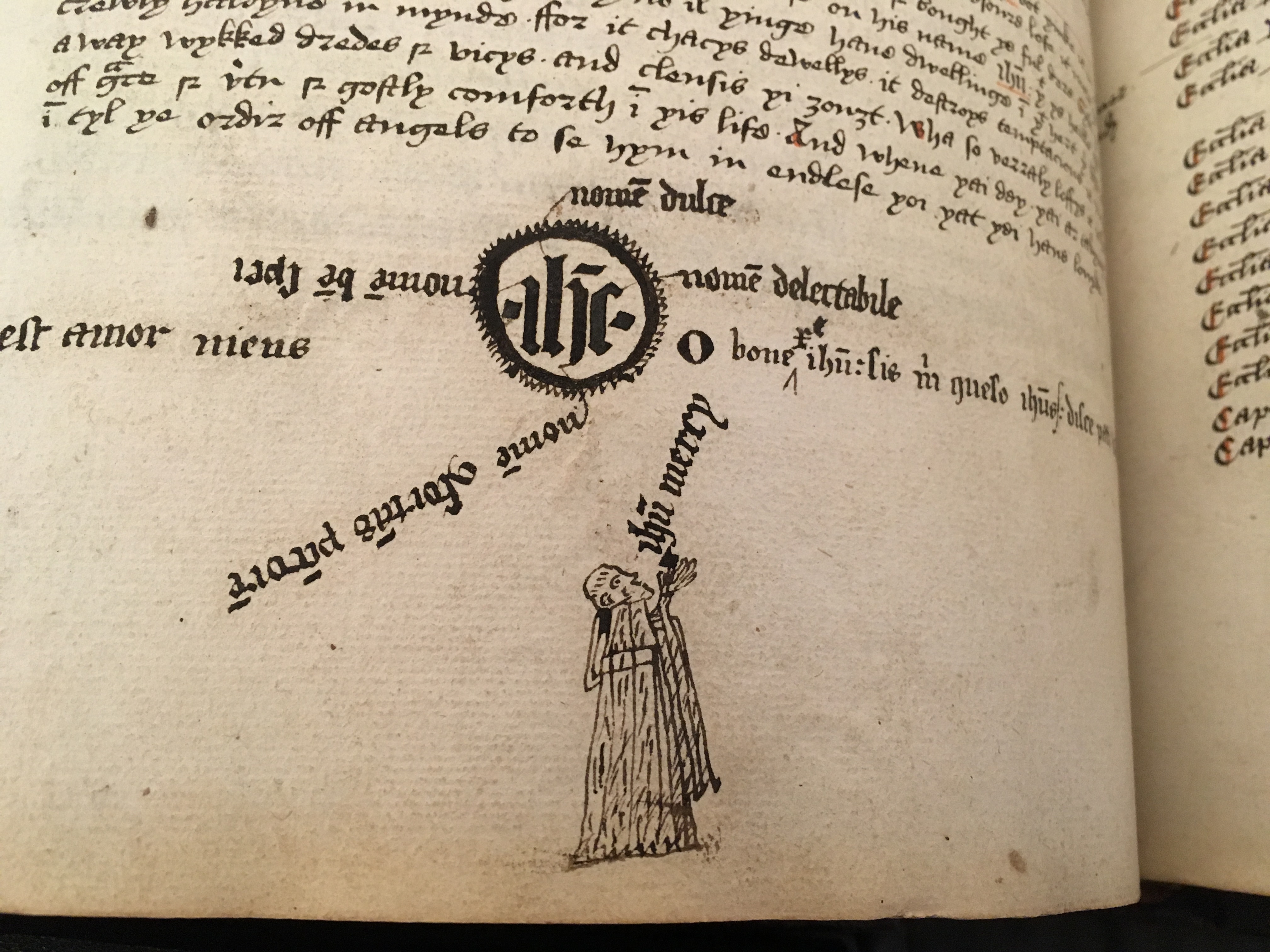

I walk out of the cathedral via the cloisters, stripped bare of benches and cupboards by the time of Dean Toby Matthews in the 1590s. Those benches and cupboards would once have been where the books were kept. I keep seeing annotations saying that the book had been placed in the ninth cupboard in the 1510s – it seems to have been where the new books were put, rather like a new books display in a library today. Finally, as I’m about to step out into the spring sunshine, I hear a choir rehearsal drifting through the cathedral from the quire. John Brimley, the last lay cantor (music master), stayed on through the Reformation to teach the choirboys and play the organs. He is buried in the Galilee Chapel, after a lifetime of making sure that there was music at Durham. The music he taught the choirboys changed with the Reformation and changed again through the seventeenth century and beyond, but here too the spaces and tasks would be recognizable today.

I always find it difficult to get the balance right- the empathy to understand the past and to make it understandable today, but also to maintain a sense of distance to respect its differences and to be clear-sighted about it. At Durham, I get to consciously think about overlapping usages, the ways in which the needs of generations of occupiers have remade the buildings into what we see today and especially how the changing needs of the sixteenth century shaped the survival of the medieval cathedral.